-

UK Intellectual Property Office (IPO) said that Japanese conglomerate Toshiba became the first organisation to register a distinctive multimedia motion mark (a moving trademark) as per changes to the UK trademark law which came into force in January 2019.

According to the Intellectual Property Office, while it is possible to register motion marks before this, submissions needed to be illustrated graphically. The new system allows applicants to submit their moving, hologram or sound trademark by means of a multimedia file.

As per the changes in the UK trademark law, there is now a provision that makes it easier to register a sound or motion as an MP3 or MP4 file for a trademark.

Toshiba Europe communications head Matt McDowell said: We are thrilled and honoured to be the first brand to legally protect our motion mark in the UK using a multimedia graphic representation.

The Toshiba brand is synonymous with innovation and reliability and this initiative further demonstrates that our brand identity guides the business in both our communications and our behaviours in delivering our brand promise.

The graphic motif of Toshiba, which was created by the company to reflect its brand, is based on Origami, the art of paper folding.

The Japanese conglomerate applied for the multimedia motion mark through London-based Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys, Marks and Clerk.

The Intellectual Property Office said that the UKs first hologram trademark has been registered by Google under the updated law. However, the first sound mark is yet to get registered under the new system.

Intellectual Property Office chief executive Tim Moss said: Trade marks are likely to become increasingly innovative in the digital age, as organisations explore imaginative ways of reflecting their distinctive brand personalities using creative intellectual property.

Under the amended trade mark law, submission of motion marks, hologram trade marks and sound marks via multimedia format now enables examiners to see exactly what the creator of the mark intended.

The Intellectual Property Office is the official UK government body that handles intellectual property (IP) rights, which includes patents, designs, trademarks and copyrigh .

McDonald’s Corp has lost its rights to the trademark “Big Mac” in a European Union case ruling in favor of Ireland-based fast-food chain Supermac’s, according to a decision by European regulators.

As per judgment revoked McDonald’s registration of the trademark, saying that the world’s largest fast-food chain had not proven genuine use of it over the five years prior to the case being lodged in 2017.

The Spain-based EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) did not respond to phone calls and emails requesting comment. McDonald’s was not immediately available to comment on the decision, which the company can still appeal.

The ruling allows other companies as well as McDonald’s to use the “Big Mac” name in the EU.

Supermac’s said it can now expand in the United Kingdom and Europe. It said it had never had a product called “Big Mac” but that McDonald’s had used the similarity of the two names to block the Irish chain’s expansion.

“Supermac’s are delighted with their victory in the trademark application and in revoking the Big Mac trademark which had been in existence since 1996,” founder Pat McDonagh told Reuters in an email.

“This is a great victory for business in general and stops bigger companies from “trademark bullying” by not allowing them to hoard trademarks without using them.”

McDonald’s, which sells its flagship “Big Mac” burgers internationally, submitted printouts of European websites as evidence, as well as posters, packaging, and affidavits from company representatives attesting to “Big Mac” sales in Europe.

The EUIPO said the affidavits from McDonald’s needed to be supported by other types of evidence, and that the websites and other promotional materials did not provide that support.

From the website printouts “it could not be concluded whether, or how, a purchase could be made or an order could be placed,” the EUIPO said. “Even if the websites provided such an option, there is no information of a single order being placed.”

McDonald’s has historically been “extremely litigious” in the area of trademark law and typically does not lose, said Willajeanne McLean, a law professor at the University of Connecticut.

In 1993, McDonald’s won a court order blocking a dentist in New York from selling services under the name “McDental.”

In 2016, McDonald’s defeated an effort by a Singapore company to register ‘MACCOFFEE’ as an EU trademark.

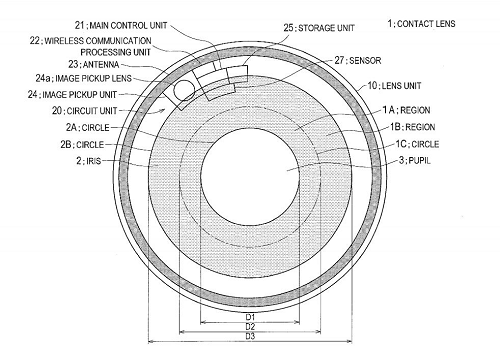

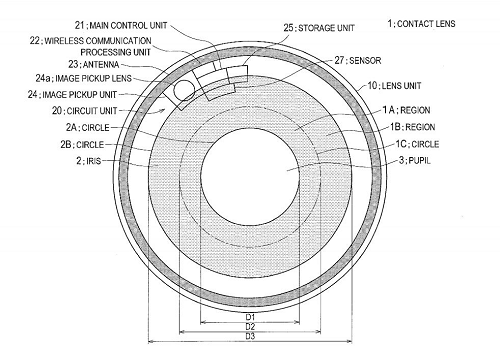

The tech giant Sony has ramped up their technology from something that weve only seen in James Bond movies, to now being our reality. The company has filed for a patent that reveals how their smart contact lenses will take pictures and record videos just with a simple blink, storing them in a small memory space on the lens or on the users eyeballs. Not only is Sony striving for this, but other tech giants such as Samsung and Google have made plans for their smart contact lenses, going public with their ideas of taking pictures, making videos and monitoring sugar intake; gamers will also experience enhanced gaming, and other possibilities are endless.

However, Sonys patent doesnt mean well be seeing them anytime soon. Nevertheless, Sonys release of the lens will contain a picture-taking unit, a central controlling unit, the main unit along with an antenna, a storage area and a piezoelectric sensor.

Image Source: C|Net A diagram of the smart lens showing different regions of the lens.

The last mentioned unit above is responsible for monitoring the time on how long the eyelids have remained opened, and it will also detect the blink that was done to take a picture, as well as the blinks that were done subconsciously. This will allow the unit to distinguish between taking pictures and a normal blink.

As mentioned in Sonys patent, the subconscious blink is between 0.2 to 0.4 seconds, thus the patent states that if the blink exceeds more than 0.5 seconds, then it was done on purpose and will be considered an unusual blinking, therefore, gesturing the unit to capture the image. The antennae will supply the power to the lens wirelessly, source it from the smartphone, a smart tablet or a computer. The technology that was first discovered by Nicola Tesla, will use either radio waves, electromagnetic induction or electromagnetic field resonance, and to top it off, the smart lens will sport an autofocus and zoom ability.

But before happy blinking customers can get their hands on this latest device, and for the intelligence agencies to blink on everything in their sight, the technology is still to go through stringent tests. Then again, a technology such as this, is an interesting concept wrapped up in the scary, depending on how it will be used

Japan Patent Office (JPO) , trail board , upheld The Boeing Company’s invalidation petition against TM Reg. no. 5990529 for the “PACHINKO&SLOT AIRPORT 777” mark in respect of amusement services in class 41 due to a likelihood of confusion with Boeing’s famous jet airliner “777”.

[Invalidation case no. 2018-890054, Gazette issue date: May 31, 2019]

AIRPORT 777

Mark in dispute, consisting of three terms, “PACHINKO&SLOT” and “AIRPORT777” in English and Japanese in three lines, and a device of jet airliner (see below), was applied for registration by SEA Co., Ltd., a Japanese business entity, on February 17, 2017 in respect of providing Pachinko and slot machine parlors, game services provided online from a computer network or mobile phone; providing amusement facilities and other services in class 41.

SEA CO., Ltd. has been operating pachinko and slot machine parlors in the name of AIRPORT 777.

Without confronting with a refusal during substantive examination, the AIRPORT 777 mark was registered on October 20, 2017.

Petition for Invalidation

Japan Trademark Law provides a provision to retroactively invalidate trademark registration for certain restricted reasons specified under Article 46 (1).

The Boeing Company, the world’s largest American aerospace company and leading manufacturer of commercial jetliners, defense, space and security systems, and service provider of aftermarket support, filed a petition for invalidation against opposed mark on July 17, 2018. Boeing argued the AIRPORT 777 mark shall be invalidated due to a likelihood of confusion with “777” The Boeing 777 when used on above designated services in class 41 based on Article 4(1)(xv) of the Trademark Law.

The Boeing 777 is the world’s largest twin-engine jet airliner, first flown in June of 1994. Commonly referred to as the ‘Triple Seven,’ the 777 is Boeing’s first fly-by-wire airliner (an electronic system that replaces the conventional manual flight controls of an aircraft) and the first commercial aircraft entirely computer-designed.

In Japan, Boeing has successfully registered three digits “777” in respect of jet airliners in class 12 since 2001. Trademark Registration no. 4456004 (see below).

Board decision

The Board admitted that the “777” mark has acquired a high degree of popularity and reputation as a source indicator of Boeing jetliners among relevant consumers.

In assessment of the similarity between two marks, at the outset the Board found that three digits 777 implies a meaning of wining jackpot in association with pachinko and slot machines. However, by taking account of a term “AIRPORT” and a silhouette of jet airliner, the Board considered it is likely that relevant consumers with an ordinary care shall connect or associate the services using opposed mark with The Boeing 777. If so, it is unquestionable that opposed mark is highly similar to a famous mark “777”. Besides, since recent game and amusement industry have a trend to introduce flight and airplane games with new technology or to use images, video and sounds of jet airliner, it is not unreasonable to find above services in class 41 are closely related to jet airliners. In view of Boeing’s business portfolio, it is highly predictable that The Boeing Company expands the business and launches amusement business.

Based on the foregoing, the Board concluded that, from totality of circumstances and evidences, relevant traders or consumers are likely to confuse or misconceive a source of opposed mark with Boeing or any entity systematically or economically connected with the opponent and declared invalidation based on Article 4(1)(xv).

Wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris, France , named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built the tower.

You can almost never find videos or photos of the Eiffel Tower at night on stock sites. Why is this? Because the Eiffel Tower is copyrighted when those lights are twinkling in the night sky. This 4-minute video from Half as Interesting explains why.European Union copyright law states that an artistic work (that could be a photo, video, song, or building) is protected during the lifetime of its creator, plus another 70 years.

Most countries have a “freedom of panorama” law, which allows you to photograph a skyline and include copyrighted buildings in your shot. So while you’d be perfectly okay capturing a photo of Big Ben in London, you just couldn’t go off and build a brand new version in your backyard without infringing copyright.

But the EU allows countries to opt-out of including this freedom of panorama clause in their copyright laws. France has chosen to utilize this exception.

The copyright owner and creator of the Eiffel Tower died in 1923, so in 1993 the image of the Eiffel Tower entered into the public domain. That’s why Las Vegas has its own Eiffel Tower, built in 1999.

But the lights were not installed until 1985 and, since they’re considered an artistic work, they are well within their copyright protection period.

The same applies for the Louvre and Rome’s main train station. While no one has ever gone to court for a night-time Eiffel Tower snap, that could change at any time.“Technically taking the picture is also illegal, but it’s the sharing part that will land you in hot water,” Metro writes. “If you want to publish the image to social media you must gain permission from the ‘Société d’Exploitation de la Tour Eiffel’ (the Eiffel Tower’s operating company).”We previously wrote about this same topic back in 2014.

The Spotify litigation (covered here) centres around the question that has been simmering around the Indian copyright scene for some time – does the statutory licensing regime under section 31D cover internet streaming services such as Spotify or Saavn?

While legal opinion seemed to be divided on the issue, the Central Government through the Department of Industrial Policy & Promotion released an ‘Office Memorandum’ (‘OM’) on September 5, 2016 regarding the inclusion of ‘Internet Broadcasting Organisations’ under the purview of statutory licensing as per s 31D of the Copyright Act, 1957 (‘the Act’).

The effect of this OM was that the owners of copyright would be bound by the rates of royalty as fixed by the Copyright Board for internet-based streaming rights of a particular work. Two issues arise out of the OM: Does the Central Government have the right to issue such an OM and is it binding? Is the OM legally sound?

Central Government’s power to issue the OM

The Act sets up two main bodies to administer it, namely the Copyright Office and the Copyright Board. Certain functions are given specifically to the Copyright Office, which is headed by the Registrar of Copyrights and his subordinates, and other powers, mostly adjudicatory or quasi-judicial in nature, are given to the Copyright Board.

The principal function of the Copyright Office is to maintain a Register of Copyrights of the names, addresses of authors and owners of the Copyright for the time being and other relevant particulars may be entered. As per s 9 of the Act, the Copyright Office is under the immediate control of the Registrar of Copyrights who in turn shall act under the superintendence and direction of the Central Government.

On the other hand, the Copyright Board, set up under s 11 of the Act, is an independent body, and is not under the direction or supervision of the Central Government. It has been held to be a quasi-judicial body by the Supreme Court in the Super Cassettes judgment and by the Madras High Court in the South Indian Music Companies Association judgment. In fact, the Madras High Court held that in the selection committee and process of selection of members to the Copyright Board, primacy must be given to the judiciary. This shows that as far as the powers and functions given to the Copyright Board are concerned, it is meant to act as a body outside the control and supervision of the Central Government. There is, in other words, a separation of powers between the Copyright Office and the Copyright Board.

S 31D of the Act dealing with statutory licensing is administered by the Copyright Board and must be, as a corollary, interpreted only by the Copyright Board and the judiciary. The Central Government has no role in either administering or interpreting it. The Central Government has no right to issue any clarification, memorandum, notification or any other such note that ‘interprets’ or ‘clarifies’ s 31D.

The Government’s power is, in fact, much narrower. Unlike s 119 of the Income Tax Act, 1961 or similar such provisions in the other taxing statutes, there is no express provision in the Copyright Act, 1957 which empowers the Central Government to issue instructions or orders or clarifications regarding any statutory provision. Although the Act states that Registrar of Copyrights shall act under the “superintendence and direction” of the Central Government, it is clear that such “superintendence and direction” does not envisage the power to issue clarificatory statements.

Now, let us look at the merits of the OM.

Legislative intent

The HRD Minister, at the time of passing the bill introducing section 31D in the Parliament in his speech had stated that:

“The Copyright Board, as a matter of law, under the statute will actually decide on the quantum of money that will be required to be paid by the TV companies to the music companies who have bought over those rights. Therefore, there was some debate as to whether it should be limited only to radio, and TV should be kept out of it. But ultimately, we decided that TV should be included in it.”

From a plain reading of the speech of the HRD Minister, it is very evident that the only debate was if the provisions of s 31D should be limited only to radio or should include the TV broadcasters and it was never the intention of the Legislature to include internet broadcasters within the ambit of this section. Any attempt to do so will be against the spirit of the amendment.

Further, s 31D (3) clearly states that different rates may be set for “radio and TV” broadcasting. No other form of broadcasting is envisaged. Further, r 29 of the Copyright Rules, 2013 (‘Rules’) sets the procedure for the application for a statutory licence. R 29(3) states that “Separate notices shall be given… for radio broadcast or television broadcast…”. R 29(4), which deals with the details to be provided by the applicant states that the applicant must provide the “Name of the channel”, the “territorial coverage… by way of radio broadcast, television broadcast…”, and the “mode of communication to public, i.e radio, television or performance”. Even in r 30 relating to the maintenance of records, the rule states that separate records shall be maintained for “radio and television broadcasting”. R 31(6) of the Rules reiterates s 31D(3) when it states that the Board shall determine “royalties payable… for radio and television broadcast separately.” Lastly, r 31(7) makes a specific reference to the terms and conditions of the ‘Grant of Permission Agreement (GOPA)’ between the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting for operating the radio station.

All these provisions further show that the intent of the legislature in introducing s 31D was to regulate the licence rates for radio and television broadcasting only and not any dissemination of music through the internet.

The meaning of the terms ‘broadcasting organisation’, ‘broadcast’ and ‘communication to the public’

The OM attempts to include internet broadcasting within the ambit of s 31D(1) by reading the section with the definition of ‘communication to the public’ which is defined under Section 2(ff) of the Act. This approach is inherently erroneous.

S 31D(1) refers to a ‘broadcasting organisation’. This expression has not been defined under the Act. However, s 2(dd) introduced in 2012, defines “broadcast” as follows:

“broadcast” means communication to the public—

- (i) by any means of wireless diffusion, whether in any one or more of the forms of signs, sounds or visual images; or

- (ii) by wire,

and includes a re-broadcast;

The definition of ‘broadcast’ has two key ingredients: (a) there must be a communication to the public; and (b) this communication must be through wireless diffusion or by wire. A close reading of this provision shows that a broadcast is the act of actually transmitting the copyrighted work through wire or wireless diffusion, and not merely making it ready for such diffusion.

The term “communication to the public” is wider than “broadcast” since the definition of “broadcast” only includes two methods of communicating the work to the public. The phrase ‘communication to the public’ is defined as under:

‘(ff) “communication to the public” means making any work or performance available for being seen or heard or otherwise enjoyed by the public directly or by any means of display or diffusion other than by issuing physical copies of it, whether simultaneously or at places and times chosen individually, regardless of whether any member of the public actually sees, hears or otherwise enjoys the work or performance so made available.

Explanation.-For the purposes of this clause, communication through satellite or cable or any other means of simultaneous communication to more than one household or place of residence including residential rooms of any hotel or hostel shall be deemed to be communication to the public;’;”

The definition of “communication to the public” contains a phrase ‘whether simultaneously or at places and times chosen individually’. The question is – who makes this choice, the owner of the copyright or the member of the public? If the choice is that of the owner, then communication will exclude streaming. But if it implies the choice of the consumer, then it will include streaming.

The phrase immediately preceding this, being “making any work or performance available”, obviously refers to the owner of the copyright making it available. The phrase “whether simultaneously…” only qualifies this “making… available”. Further, every time a phrase refers to the “public”, the “public” is intentionally invoked by the definition. The person to whom no reference is made directly, is the person “making” the communication, i.e. the owner. Therefore, I submit that “chosen individually” intends to cover only the owner of the work and not the consumer. In other words, for an act to amount to communication to the public, the communication must be at times and places chosen by the owner.

This brings us to two questions:

- Then where is internet streaming covered?

- Then what is the meaning of “individually”?

To answer the first question, when the owner of a sound recording gives internet streaming services for music, he gives that person a licence to do two things: (a) to make a copy of that work on a server belonging to the streaming service; and (b) to allow the streaming service to “rent” it to the consumer.

These rights are covered under s 14(d)(i) and s 14(d)(ii). Communication of the work to the public is not invoked at all. For this reason also, the dissemination of music through an internet music streaming service provider is not a ‘communication to the public’, and is therefore not covered by the definition of ‘broadcast’ under s 2(ff). Such a reading is consistent with the entire scheme of the Act that deals with broadcasting, but only refers to radio and TV.

To answer the second question, “communication of the public” covers a broader spectrum than just broadcast. It includes theatrical distribution, public performance, narrowcasting – all these are cases where the owner chooses the times and places of communication. In fact, the Madras High Court in Thiagarajan Kumararaja v Capital Film Works, even found that dubbing and subtitling of films comes under the ambit of section 2(ff). This shows that the term “places and times chosen individually” will not become meaningless if internet streaming is excluded from its ambit.

To summarise, where the owner of the work chooses the times and places, it is “communication to the public”. Where the consumer chooses the times and places, it is not “communication to the public”. Therefore, persons running internet music streaming services are not ‘broadcasting organisations’ and will not be covered by section 31D. This would imply, obviously, that internet radio would be “communication to the public”. But the services provided by Spotify are not internet radio – the choice of what song to play and when is with the consumer. Therefore, it is not relevant to the present discussion.

What I attempt above is an internal reading of the Act and the Rules. Should statutory licensing include internet broadcasting? That is for policymakers to argue. The arguments above, I believe, are sound. But I would not be surprised if a judge leaned the other way on a reading of section 2(ff). Either way, Spotify’s action of invoking section 31D and playing the music without a licence is indefensible in law. That has already been covered on this blog before. Spotify, I think, is playing litigation strategy – try and get an interim order out of a judge and push Warner to a settlement. ( source IPspicy ) .

The move comes after the Trump administration put Huawei on a blacklist last month.

China’s Huawei has applied to trademark its “Hongmeng” operating system (OS) in at least nine countries and Europe, data from a UN body shows, in a sign it may be deploying a back-up plan in key markets as US sanctions threaten its business model.

China’s Huawei has applied to trademark its “Hongmeng” operating system (OS) in at least nine countries and Europe, data from a UN body shows, in a sign it may be deploying a back-up plan in key markets as US sanctions threaten its business model.

The move comes after the Trump administration put Huawei on a blacklist last month that barred it from doing business with US tech companies such as Alphabet, whose Android OS is used in Huawei’s phones.

Since then, Huawei – the world’s biggest maker of telecoms network gear – has filed for a Hongmeng trademark in countries such as Cambodia, Canada, South Korea and New Zealand, data from the UN World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) shows.

• Huawei May Name Its Android, Windows Replacement as ‘Ark OS’

It also filed an application in Peru on May 27, according to the country’s anti-trust agency Indecopi.

Huawei has a back-up OS in case it is cut off from US-made software, Richard Yu, CEO of the firm’s consumer division, told German newspaper Die Welt in an interview earlier this year. The firm, also the world’s second-largest maker of smartphones, has not yet revealed details about its OS.

Its applications to trademark the OS show Huawei wants to use “Hongmeng” for gadgets ranging from smartphones, portable computers to robots and car televisions.At home, Huawei applied for a Hongmeng trademark in August last year and received a nod last month, according to a filing on China’s intellectual property administration’s website.

Huawei declined to comment.

Consumer concerns

According to WIPO data, the earliest Huawei applications to trademark the Hongmeng OS outside China were made on May 14 to the European Union Intellectual Property Office and South Korea, or right after the United States flagged it would stick Huawei on an export blacklist.Huawei has come under mounting scrutiny for over a year, led by US allegations that “back doors” in its routers, switches and other gear could allow China to spy on US communications.

The company has denied its products pose a security threat.

However, consumers have been spooked by how matters have escalated, with many looking to offload their devices on worries they would be cut off from Android updates in the wake of the US blacklist.

Huawei’s hopes to become the world’s top-selling smartphone maker in the fourth quarter this year have now been delayed, a senior Huawei executive said this week.

Peru’s Indecopi has said it needs more information from Huawei before it can register a trademark for Hongmeng in the country, where there are some 5.5 million Huawei phone users.The agency did not give details on the documents it had sought, but said Huawei had up to nine months to respond.Huawei representatives in Peru declined to provide immediate comment, while the Chinese embassy in Lima did not respond to requests for comment. (source NDTV ).

New Delhi, on April 28 India intends to make its Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) policy more efficient and speedier, Commerce Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said on Thursday. India intends to make its Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) policy more efficient and speedier, Commerce Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said on Thursday.

“The mindset of the government is to make the IPR policy more efficient and speedier,” she said, while addressing the World Intellectual Property Day celebrations here. She also gave away the National Intellectual Property Awards on the occasion

“India’s IPR policy is TRIPS (Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights) Acompliant and forward looking,” she said.

Sitharaman also said creating awareness is very important, and launching an IPR Awareness campaign in schools across the country by Cell for IPR Promotion and Management (CIPAM) is a step in creating a mindset and respect for innovation right from the schools.

On Tuesday, the CIPAM, in collaboration with the International Trademark Association (INT), started an IPR awareness campaign in schools from one such institution in the national capital.

A Union Commerce Ministry release here said that a programme is being worked out to conduct over 3,500 IPR awareness programmes in schools, universities and industries across the country, including in Tier 1, 2, and 3 cities, as well as in rural areas, along with translating content into various regional languages for a wider reach.

Earlier this week, the government extended the Start-Ups Intellectual Property Protection (SIPP) scheme for three years till March 2020 to ensure protection of entrepreneurs’ patents, trademark and designs.

In a signal that China may soften its stand against social networking giant Facebook, the Beijing High Court has ruled in favour of the Cupertino-based company, saying that a Chinese company should not have been allowed to register the “face book” trademark back in 2014. Beijing, May 9: In a signal that China may soften its stand against social networking giant Facebook, the Beijing High Court has ruled in favour of the Cupertino-based company, saying that a Chinese company should not have been allowed to register the “face book” trademark back in 2014.

The Zhongshan Pearl River Drinks Factory in southern Guangdong province that had registered the brand name “face book,” produces food products like potato chips and canned vegetables. “Under the Chinese law, a multinational with a globally-recognised brand must prove that its trademark is also well known within China,”

The Financial Times reported on Monday.(ALSO READ:Apple loses Chinese lawsuit over iPhone name).Along with other social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook is currently blocked to nearly 700 million internet users in China. Burt several many people are using virtual private networks (VPNs) which allow them to circumvent the “Great Firewall” to access the site.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has been trying to break the ice with China for years. He met Chinese President Xi Jinping during his visit to the US last year.The Facebook founder has also met China’s chief censor officer at his home in San Francisco and reportedly had a meeting with the head of the ruling Communist party’s propaganda apparatus.

In March this year, Zuckerberg was seen jogging through Tiananmen Square with the famous gate to the Forbidden City imperial palace in the background. He was in Beijing to attend the China Development Forum 2016. Zuckerberg also met Alibaba Group Holdings’s executive chairman Jack Ma and discussed about innovation during the visit. Ma said Zuckerberg respected Chinese culture, adding that oriental culture and western culture should learn from each other and work collaboratively for a better future.

Last week, Apple lost an appeal in China for its iPhone trademark when a lower court ruled that a Chinese company Xintong Tiandi can use the “iPhone” mark on its leather goods.

“Apple is disappointed the Beijing Higher People’s Court chose to allow Xintong to use the ‘iPhone’ mark for leather goods when we have prevailed in several other cases against Xintong,” the company said in a statement.

“We intend to request a retrial with the Supreme People’s Court and will continue to vigorously protect our trademark rights. We work hard to make the best products in the world and want to ensure our customers’ experience is not compromised by companies who try to profit from using our brand,” Apple added.

Apple was set to appeal against the verdict in a higher court.

China’s Huawei has applied to

China’s Huawei has applied to