There’s more data to relate than there is instrument-panel real estate, so Volvo came up with a solution . . .

olvo is taking head-up displays to a whole new level, according to this application the automaker has filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. And when we say whole new level, we mean both literally and figuratively, because this patent involves a head-up display that’s not on the windshield, but on the roof of the car.

The patent application, which has a filing date of August 13, 2019, is assigned to Volvo Car Corporation, erasing all doubts as to which branch of Volvo the system could be applied to. Most HUDs use a series of mirrors in conjunction with a projector to display an image in front of the driver on the windshield; Volvo’s patent is no different, except for the location of the system.

The patent illustrations show a projector system right above the driver that displays information about the car on an “optically transmissive roof window.” We believe the reason that Volvo doesn’t just call it “glass” is probably that the company will modify the glass to allow for better projection in all light conditions. If you’ve ever driven a vehicle with the HUD active while wearing sunglasses, you would have noticed that it can be hard to see the image being displayed. Perhaps Volvo is trying to tackle the issue through the use of an auto-dimming glass or variable-opacity electrochromic glass, which we recently experienced on the 2019 McLaren 720S Spider. As far as the projection system goes, Volvo says it will most likely be LED based, with options for brightness and position customization based on driver preference.

We can only guess what would be displayed up there. It would most likely be nonessential info, given that it’s not a great idea to take your eyes off the road while driving. Volvo states that the reason for the invention is to declutter the front display systems and reduce the number of pages that need to be dug through to find certain information. As cars get more complex, there is more and more information available to drivers, but the space in which it can be displayed has stayed the same for the past 60 years.

One cool feature that Volvo mentions in the patent is the ability to check the vehicle’s status without actually having to go back outside and into the vehicle. The company claims that when the system is on, anyone could look down at the roof from a vantage point above the car (like the second floor of a home or buildling) and know if the car is locked or, in the case of an EV, the battery life and charge status.

Another possibility for a roof HUD system might be for autonomous driving. Drivers who decide to sit back and and let the car drive itself could look up for information about their speed, distance, and time of arrival. This patent does precede Volvo’s plan for Level 4 autonomy by 2021, so there is a strong likelihood of this roof HUD system debuting soon on a concept car.

We’re curious to see what the final product looks like, and how it works, and just how much our necks will hurt to look at it.

New Delhi: A patent right will rest with the academic institution if a student, researcher or faculty member has used its resources and funds for developing a product, according to draft guidelines floated by the government on the implementation of IPR policy for academic institutions.

However, if an institution determines that an invention was made by an individual on his or her own time and unrelated to his or her responsibilities towards the institution and was conceived without use .. of its resources, then the invention shall vest with the individual or inventor.

These guidelines are floated with an objective to foster innovation and creativity in the areas of technology, sciences, and humanities by nurturing new ideas and research, in an ethical environment.

It would also help in protecting intellectual property rights (IPRs) generated by faculty or personnel, students, and staff of the academic institution, by translating their creative and innovative work into IP rights.

“The ownership rights on IP may vary according to the context in which the concerned IP was generated. In this regard, a two-tier classification is suggested for adoption,” it said.

In case of copyright, the draft has suggested that the ownership rights in scholarly and academic works generated utilising resources of academic institution, including books, dissertations and lecture notes, shall ordinarily be vested with the author.

On the other hand, the ownership rights in lecture videos or massive open online courses, films, plays, and musical works, shall ordinarily be vested with the academic institution.

Similarly, ownership rights over integrated circuits and plant varieties; and industrial designs will rest with the academic institution if a student, researcher or faculty member have used its resources and funds for developing the product.

The guidelines also said the academic institution is free to enter into revenue sharing agreement with the researcher, in cases of commercialisation of innovation, and creation as per the advice of IP Cell.

It added that the academic institution may appoint a committee of experts to address the concerns of the aggrieved person and all disputes shall be dealt with by this committee.

It has also suggested creation of IP Cells in academic institutions to ensure the effective applicability of these guidelines.

The Cell will be responsible for conducting awareness programmes for students, faculty, researchers, and officials. Besides, it would conduct advanced-level awareness programmes.

“IP Cell shall provide an environment for academic and R&D (research and development) excellence and conduct dedicated programmes on IPR for the undergraduate and postgraduate courses. ..

The other objectives of these guidelines include laying down an efficient, fair, and transparent administrative process for ownership control and assignment of IP rights and sharing of revenues generated by IP, created and owned by the academic institution.

“These guidelines shall apply to all IP created at the academic institution, as well as, all IP rights associated with them, from the date of implementation of these norms,” it added.

The 23-page model guidelines on implementation of IPR policy in Academic Institution have been prepared by the Cell for IPR Promotion & Management (CIPAM), under the commerce and industry ministry.

The IPRs are statutory rights. Owners of these exclusive rights get protection for a specified period of time like 20 years in case of patents. These rights include copyrights, Patents trademarks, geographical indications, and industrial designs.

Singapore is the first country in the world , launch computer application for trademark Registration , by the easy process you can file your trade mark application within 10 minutes .

A new mobile app touted as the worlds first trademark registration mobile app will allow businesses and entrepreneurs to file their trademarks directly with the Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS) on their mobile devices.

Named IPOS Go, the app has a simplified user interface and features that will allow for a faster and easier application process, IPOS said.

With the app, a trademark can be filed in less than 10 minutes, a small fraction of the current 45 to 60 minutes IPOS said.

Filing costs will also be significantly reduced as applicants may feel more confident in filing their applications directly with IPOS, the authority said.

Available on the Apple App store and Google Play, the app will also allow applicants to track their registration status, be notified of important updates, as well as file for trademark renewals.

IPOS Go also uses artificial intelligence (AI) technology to help prevent applicants from filing for trademarks that are too similar to existing ones. IPOS said that more than 40 per cent of trademarks filed in the world today contain images.

As the world continues to see a surge in trademarks filings, the new AI capability will help business owners better manage their brands, it said.

According to IPOS, trademark applications in Singapore have increased by 30 per cent over the last five years.

-

UK Intellectual Property Office (IPO) said that Japanese conglomerate Toshiba became the first organisation to register a distinctive multimedia motion mark (a moving trademark) as per changes to the UK trademark law which came into force in January 2019.

According to the Intellectual Property Office, while it is possible to register motion marks before this, submissions needed to be illustrated graphically. The new system allows applicants to submit their moving, hologram or sound trademark by means of a multimedia file.

As per the changes in the UK trademark law, there is now a provision that makes it easier to register a sound or motion as an MP3 or MP4 file for a trademark.

Toshiba Europe communications head Matt McDowell said: We are thrilled and honoured to be the first brand to legally protect our motion mark in the UK using a multimedia graphic representation.

The Toshiba brand is synonymous with innovation and reliability and this initiative further demonstrates that our brand identity guides the business in both our communications and our behaviours in delivering our brand promise.

The graphic motif of Toshiba, which was created by the company to reflect its brand, is based on Origami, the art of paper folding.

The Japanese conglomerate applied for the multimedia motion mark through London-based Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys, Marks and Clerk.

The Intellectual Property Office said that the UKs first hologram trademark has been registered by Google under the updated law. However, the first sound mark is yet to get registered under the new system.

Intellectual Property Office chief executive Tim Moss said: Trade marks are likely to become increasingly innovative in the digital age, as organisations explore imaginative ways of reflecting their distinctive brand personalities using creative intellectual property.

Under the amended trade mark law, submission of motion marks, hologram trade marks and sound marks via multimedia format now enables examiners to see exactly what the creator of the mark intended.

The Intellectual Property Office is the official UK government body that handles intellectual property (IP) rights, which includes patents, designs, trademarks and copyrigh .

McDonald’s Corp has lost its rights to the trademark “Big Mac” in a European Union case ruling in favor of Ireland-based fast-food chain Supermac’s, according to a decision by European regulators.

As per judgment revoked McDonald’s registration of the trademark, saying that the world’s largest fast-food chain had not proven genuine use of it over the five years prior to the case being lodged in 2017.

The Spain-based EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) did not respond to phone calls and emails requesting comment. McDonald’s was not immediately available to comment on the decision, which the company can still appeal.

The ruling allows other companies as well as McDonald’s to use the “Big Mac” name in the EU.

Supermac’s said it can now expand in the United Kingdom and Europe. It said it had never had a product called “Big Mac” but that McDonald’s had used the similarity of the two names to block the Irish chain’s expansion.

“Supermac’s are delighted with their victory in the trademark application and in revoking the Big Mac trademark which had been in existence since 1996,” founder Pat McDonagh told Reuters in an email.

“This is a great victory for business in general and stops bigger companies from “trademark bullying” by not allowing them to hoard trademarks without using them.”

McDonald’s, which sells its flagship “Big Mac” burgers internationally, submitted printouts of European websites as evidence, as well as posters, packaging, and affidavits from company representatives attesting to “Big Mac” sales in Europe.

The EUIPO said the affidavits from McDonald’s needed to be supported by other types of evidence, and that the websites and other promotional materials did not provide that support.

From the website printouts “it could not be concluded whether, or how, a purchase could be made or an order could be placed,” the EUIPO said. “Even if the websites provided such an option, there is no information of a single order being placed.”

McDonald’s has historically been “extremely litigious” in the area of trademark law and typically does not lose, said Willajeanne McLean, a law professor at the University of Connecticut.

In 1993, McDonald’s won a court order blocking a dentist in New York from selling services under the name “McDental.”

In 2016, McDonald’s defeated an effort by a Singapore company to register ‘MACCOFFEE’ as an EU trademark.

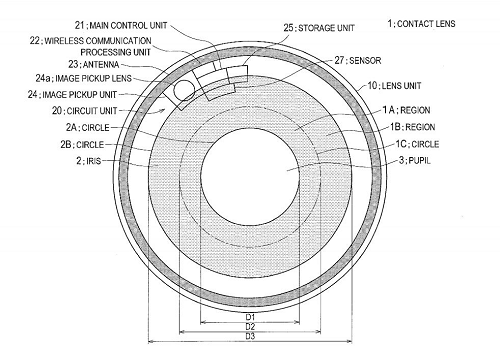

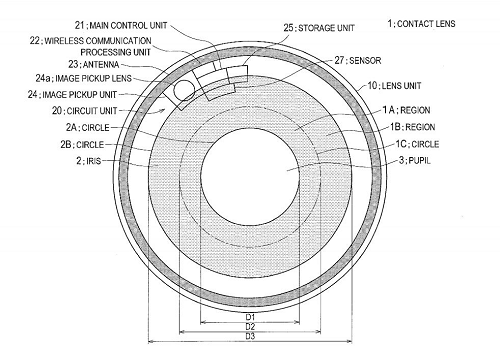

The tech giant Sony has ramped up their technology from something that weve only seen in James Bond movies, to now being our reality. The company has filed for a patent that reveals how their smart contact lenses will take pictures and record videos just with a simple blink, storing them in a small memory space on the lens or on the users eyeballs. Not only is Sony striving for this, but other tech giants such as Samsung and Google have made plans for their smart contact lenses, going public with their ideas of taking pictures, making videos and monitoring sugar intake; gamers will also experience enhanced gaming, and other possibilities are endless.

However, Sonys patent doesnt mean well be seeing them anytime soon. Nevertheless, Sonys release of the lens will contain a picture-taking unit, a central controlling unit, the main unit along with an antenna, a storage area and a piezoelectric sensor.

Image Source: C|Net A diagram of the smart lens showing different regions of the lens.

The last mentioned unit above is responsible for monitoring the time on how long the eyelids have remained opened, and it will also detect the blink that was done to take a picture, as well as the blinks that were done subconsciously. This will allow the unit to distinguish between taking pictures and a normal blink.

As mentioned in Sonys patent, the subconscious blink is between 0.2 to 0.4 seconds, thus the patent states that if the blink exceeds more than 0.5 seconds, then it was done on purpose and will be considered an unusual blinking, therefore, gesturing the unit to capture the image. The antennae will supply the power to the lens wirelessly, source it from the smartphone, a smart tablet or a computer. The technology that was first discovered by Nicola Tesla, will use either radio waves, electromagnetic induction or electromagnetic field resonance, and to top it off, the smart lens will sport an autofocus and zoom ability.

But before happy blinking customers can get their hands on this latest device, and for the intelligence agencies to blink on everything in their sight, the technology is still to go through stringent tests. Then again, a technology such as this, is an interesting concept wrapped up in the scary, depending on how it will be used

Japan Patent Office (JPO) , trail board , upheld The Boeing Company’s invalidation petition against TM Reg. no. 5990529 for the “PACHINKO&SLOT AIRPORT 777” mark in respect of amusement services in class 41 due to a likelihood of confusion with Boeing’s famous jet airliner “777”.

[Invalidation case no. 2018-890054, Gazette issue date: May 31, 2019]

AIRPORT 777

Mark in dispute, consisting of three terms, “PACHINKO&SLOT” and “AIRPORT777” in English and Japanese in three lines, and a device of jet airliner (see below), was applied for registration by SEA Co., Ltd., a Japanese business entity, on February 17, 2017 in respect of providing Pachinko and slot machine parlors, game services provided online from a computer network or mobile phone; providing amusement facilities and other services in class 41.

SEA CO., Ltd. has been operating pachinko and slot machine parlors in the name of AIRPORT 777.

Without confronting with a refusal during substantive examination, the AIRPORT 777 mark was registered on October 20, 2017.

Petition for Invalidation

Japan Trademark Law provides a provision to retroactively invalidate trademark registration for certain restricted reasons specified under Article 46 (1).

The Boeing Company, the world’s largest American aerospace company and leading manufacturer of commercial jetliners, defense, space and security systems, and service provider of aftermarket support, filed a petition for invalidation against opposed mark on July 17, 2018. Boeing argued the AIRPORT 777 mark shall be invalidated due to a likelihood of confusion with “777” The Boeing 777 when used on above designated services in class 41 based on Article 4(1)(xv) of the Trademark Law.

The Boeing 777 is the world’s largest twin-engine jet airliner, first flown in June of 1994. Commonly referred to as the ‘Triple Seven,’ the 777 is Boeing’s first fly-by-wire airliner (an electronic system that replaces the conventional manual flight controls of an aircraft) and the first commercial aircraft entirely computer-designed.

In Japan, Boeing has successfully registered three digits “777” in respect of jet airliners in class 12 since 2001. Trademark Registration no. 4456004 (see below).

Board decision

The Board admitted that the “777” mark has acquired a high degree of popularity and reputation as a source indicator of Boeing jetliners among relevant consumers.

In assessment of the similarity between two marks, at the outset the Board found that three digits 777 implies a meaning of wining jackpot in association with pachinko and slot machines. However, by taking account of a term “AIRPORT” and a silhouette of jet airliner, the Board considered it is likely that relevant consumers with an ordinary care shall connect or associate the services using opposed mark with The Boeing 777. If so, it is unquestionable that opposed mark is highly similar to a famous mark “777”. Besides, since recent game and amusement industry have a trend to introduce flight and airplane games with new technology or to use images, video and sounds of jet airliner, it is not unreasonable to find above services in class 41 are closely related to jet airliners. In view of Boeing’s business portfolio, it is highly predictable that The Boeing Company expands the business and launches amusement business.

Based on the foregoing, the Board concluded that, from totality of circumstances and evidences, relevant traders or consumers are likely to confuse or misconceive a source of opposed mark with Boeing or any entity systematically or economically connected with the opponent and declared invalidation based on Article 4(1)(xv).

The Spotify litigation (covered here) centres around the question that has been simmering around the Indian copyright scene for some time – does the statutory licensing regime under section 31D cover internet streaming services such as Spotify or Saavn?

While legal opinion seemed to be divided on the issue, the Central Government through the Department of Industrial Policy & Promotion released an ‘Office Memorandum’ (‘OM’) on September 5, 2016 regarding the inclusion of ‘Internet Broadcasting Organisations’ under the purview of statutory licensing as per s 31D of the Copyright Act, 1957 (‘the Act’).

The effect of this OM was that the owners of copyright would be bound by the rates of royalty as fixed by the Copyright Board for internet-based streaming rights of a particular work. Two issues arise out of the OM: Does the Central Government have the right to issue such an OM and is it binding? Is the OM legally sound?

Central Government’s power to issue the OM

The Act sets up two main bodies to administer it, namely the Copyright Office and the Copyright Board. Certain functions are given specifically to the Copyright Office, which is headed by the Registrar of Copyrights and his subordinates, and other powers, mostly adjudicatory or quasi-judicial in nature, are given to the Copyright Board.

The principal function of the Copyright Office is to maintain a Register of Copyrights of the names, addresses of authors and owners of the Copyright for the time being and other relevant particulars may be entered. As per s 9 of the Act, the Copyright Office is under the immediate control of the Registrar of Copyrights who in turn shall act under the superintendence and direction of the Central Government.

On the other hand, the Copyright Board, set up under s 11 of the Act, is an independent body, and is not under the direction or supervision of the Central Government. It has been held to be a quasi-judicial body by the Supreme Court in the Super Cassettes judgment and by the Madras High Court in the South Indian Music Companies Association judgment. In fact, the Madras High Court held that in the selection committee and process of selection of members to the Copyright Board, primacy must be given to the judiciary. This shows that as far as the powers and functions given to the Copyright Board are concerned, it is meant to act as a body outside the control and supervision of the Central Government. There is, in other words, a separation of powers between the Copyright Office and the Copyright Board.

S 31D of the Act dealing with statutory licensing is administered by the Copyright Board and must be, as a corollary, interpreted only by the Copyright Board and the judiciary. The Central Government has no role in either administering or interpreting it. The Central Government has no right to issue any clarification, memorandum, notification or any other such note that ‘interprets’ or ‘clarifies’ s 31D.

The Government’s power is, in fact, much narrower. Unlike s 119 of the Income Tax Act, 1961 or similar such provisions in the other taxing statutes, there is no express provision in the Copyright Act, 1957 which empowers the Central Government to issue instructions or orders or clarifications regarding any statutory provision. Although the Act states that Registrar of Copyrights shall act under the “superintendence and direction” of the Central Government, it is clear that such “superintendence and direction” does not envisage the power to issue clarificatory statements.

Now, let us look at the merits of the OM.

Legislative intent

The HRD Minister, at the time of passing the bill introducing section 31D in the Parliament in his speech had stated that:

“The Copyright Board, as a matter of law, under the statute will actually decide on the quantum of money that will be required to be paid by the TV companies to the music companies who have bought over those rights. Therefore, there was some debate as to whether it should be limited only to radio, and TV should be kept out of it. But ultimately, we decided that TV should be included in it.”

From a plain reading of the speech of the HRD Minister, it is very evident that the only debate was if the provisions of s 31D should be limited only to radio or should include the TV broadcasters and it was never the intention of the Legislature to include internet broadcasters within the ambit of this section. Any attempt to do so will be against the spirit of the amendment.

Further, s 31D (3) clearly states that different rates may be set for “radio and TV” broadcasting. No other form of broadcasting is envisaged. Further, r 29 of the Copyright Rules, 2013 (‘Rules’) sets the procedure for the application for a statutory licence. R 29(3) states that “Separate notices shall be given… for radio broadcast or television broadcast…”. R 29(4), which deals with the details to be provided by the applicant states that the applicant must provide the “Name of the channel”, the “territorial coverage… by way of radio broadcast, television broadcast…”, and the “mode of communication to public, i.e radio, television or performance”. Even in r 30 relating to the maintenance of records, the rule states that separate records shall be maintained for “radio and television broadcasting”. R 31(6) of the Rules reiterates s 31D(3) when it states that the Board shall determine “royalties payable… for radio and television broadcast separately.” Lastly, r 31(7) makes a specific reference to the terms and conditions of the ‘Grant of Permission Agreement (GOPA)’ between the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting for operating the radio station.

All these provisions further show that the intent of the legislature in introducing s 31D was to regulate the licence rates for radio and television broadcasting only and not any dissemination of music through the internet.

The meaning of the terms ‘broadcasting organisation’, ‘broadcast’ and ‘communication to the public’

The OM attempts to include internet broadcasting within the ambit of s 31D(1) by reading the section with the definition of ‘communication to the public’ which is defined under Section 2(ff) of the Act. This approach is inherently erroneous.

S 31D(1) refers to a ‘broadcasting organisation’. This expression has not been defined under the Act. However, s 2(dd) introduced in 2012, defines “broadcast” as follows:

“broadcast” means communication to the public—

- (i) by any means of wireless diffusion, whether in any one or more of the forms of signs, sounds or visual images; or

- (ii) by wire,

and includes a re-broadcast;

The definition of ‘broadcast’ has two key ingredients: (a) there must be a communication to the public; and (b) this communication must be through wireless diffusion or by wire. A close reading of this provision shows that a broadcast is the act of actually transmitting the copyrighted work through wire or wireless diffusion, and not merely making it ready for such diffusion.

The term “communication to the public” is wider than “broadcast” since the definition of “broadcast” only includes two methods of communicating the work to the public. The phrase ‘communication to the public’ is defined as under:

‘(ff) “communication to the public” means making any work or performance available for being seen or heard or otherwise enjoyed by the public directly or by any means of display or diffusion other than by issuing physical copies of it, whether simultaneously or at places and times chosen individually, regardless of whether any member of the public actually sees, hears or otherwise enjoys the work or performance so made available.

Explanation.-For the purposes of this clause, communication through satellite or cable or any other means of simultaneous communication to more than one household or place of residence including residential rooms of any hotel or hostel shall be deemed to be communication to the public;’;”

The definition of “communication to the public” contains a phrase ‘whether simultaneously or at places and times chosen individually’. The question is – who makes this choice, the owner of the copyright or the member of the public? If the choice is that of the owner, then communication will exclude streaming. But if it implies the choice of the consumer, then it will include streaming.

The phrase immediately preceding this, being “making any work or performance available”, obviously refers to the owner of the copyright making it available. The phrase “whether simultaneously…” only qualifies this “making… available”. Further, every time a phrase refers to the “public”, the “public” is intentionally invoked by the definition. The person to whom no reference is made directly, is the person “making” the communication, i.e. the owner. Therefore, I submit that “chosen individually” intends to cover only the owner of the work and not the consumer. In other words, for an act to amount to communication to the public, the communication must be at times and places chosen by the owner.

This brings us to two questions:

- Then where is internet streaming covered?

- Then what is the meaning of “individually”?

To answer the first question, when the owner of a sound recording gives internet streaming services for music, he gives that person a licence to do two things: (a) to make a copy of that work on a server belonging to the streaming service; and (b) to allow the streaming service to “rent” it to the consumer.

These rights are covered under s 14(d)(i) and s 14(d)(ii). Communication of the work to the public is not invoked at all. For this reason also, the dissemination of music through an internet music streaming service provider is not a ‘communication to the public’, and is therefore not covered by the definition of ‘broadcast’ under s 2(ff). Such a reading is consistent with the entire scheme of the Act that deals with broadcasting, but only refers to radio and TV.

To answer the second question, “communication of the public” covers a broader spectrum than just broadcast. It includes theatrical distribution, public performance, narrowcasting – all these are cases where the owner chooses the times and places of communication. In fact, the Madras High Court in Thiagarajan Kumararaja v Capital Film Works, even found that dubbing and subtitling of films comes under the ambit of section 2(ff). This shows that the term “places and times chosen individually” will not become meaningless if internet streaming is excluded from its ambit.

To summarise, where the owner of the work chooses the times and places, it is “communication to the public”. Where the consumer chooses the times and places, it is not “communication to the public”. Therefore, persons running internet music streaming services are not ‘broadcasting organisations’ and will not be covered by section 31D. This would imply, obviously, that internet radio would be “communication to the public”. But the services provided by Spotify are not internet radio – the choice of what song to play and when is with the consumer. Therefore, it is not relevant to the present discussion.

What I attempt above is an internal reading of the Act and the Rules. Should statutory licensing include internet broadcasting? That is for policymakers to argue. The arguments above, I believe, are sound. But I would not be surprised if a judge leaned the other way on a reading of section 2(ff). Either way, Spotify’s action of invoking section 31D and playing the music without a licence is indefensible in law. That has already been covered on this blog before. Spotify, I think, is playing litigation strategy – try and get an interim order out of a judge and push Warner to a settlement. ( source IPspicy ) .

The move comes after the Trump administration put Huawei on a blacklist last month.

China’s Huawei has applied to trademark its “Hongmeng” operating system (OS) in at least nine countries and Europe, data from a UN body shows, in a sign it may be deploying a back-up plan in key markets as US sanctions threaten its business model.

China’s Huawei has applied to trademark its “Hongmeng” operating system (OS) in at least nine countries and Europe, data from a UN body shows, in a sign it may be deploying a back-up plan in key markets as US sanctions threaten its business model.

The move comes after the Trump administration put Huawei on a blacklist last month that barred it from doing business with US tech companies such as Alphabet, whose Android OS is used in Huawei’s phones.

Since then, Huawei – the world’s biggest maker of telecoms network gear – has filed for a Hongmeng trademark in countries such as Cambodia, Canada, South Korea and New Zealand, data from the UN World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) shows.

• Huawei May Name Its Android, Windows Replacement as ‘Ark OS’

It also filed an application in Peru on May 27, according to the country’s anti-trust agency Indecopi.

Huawei has a back-up OS in case it is cut off from US-made software, Richard Yu, CEO of the firm’s consumer division, told German newspaper Die Welt in an interview earlier this year. The firm, also the world’s second-largest maker of smartphones, has not yet revealed details about its OS.

Its applications to trademark the OS show Huawei wants to use “Hongmeng” for gadgets ranging from smartphones, portable computers to robots and car televisions.At home, Huawei applied for a Hongmeng trademark in August last year and received a nod last month, according to a filing on China’s intellectual property administration’s website.

Huawei declined to comment.

Consumer concerns

According to WIPO data, the earliest Huawei applications to trademark the Hongmeng OS outside China were made on May 14 to the European Union Intellectual Property Office and South Korea, or right after the United States flagged it would stick Huawei on an export blacklist.Huawei has come under mounting scrutiny for over a year, led by US allegations that “back doors” in its routers, switches and other gear could allow China to spy on US communications.

The company has denied its products pose a security threat.

However, consumers have been spooked by how matters have escalated, with many looking to offload their devices on worries they would be cut off from Android updates in the wake of the US blacklist.

Huawei’s hopes to become the world’s top-selling smartphone maker in the fourth quarter this year have now been delayed, a senior Huawei executive said this week.

Peru’s Indecopi has said it needs more information from Huawei before it can register a trademark for Hongmeng in the country, where there are some 5.5 million Huawei phone users.The agency did not give details on the documents it had sought, but said Huawei had up to nine months to respond.Huawei representatives in Peru declined to provide immediate comment, while the Chinese embassy in Lima did not respond to requests for comment. (source NDTV ).

New Delhi, on April 28 India intends to make its Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) policy more efficient and speedier, Commerce Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said on Thursday. India intends to make its Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) policy more efficient and speedier, Commerce Minister Nirmala Sitharaman said on Thursday.

“The mindset of the government is to make the IPR policy more efficient and speedier,” she said, while addressing the World Intellectual Property Day celebrations here. She also gave away the National Intellectual Property Awards on the occasion

“India’s IPR policy is TRIPS (Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights) Acompliant and forward looking,” she said.

Sitharaman also said creating awareness is very important, and launching an IPR Awareness campaign in schools across the country by Cell for IPR Promotion and Management (CIPAM) is a step in creating a mindset and respect for innovation right from the schools.

On Tuesday, the CIPAM, in collaboration with the International Trademark Association (INT), started an IPR awareness campaign in schools from one such institution in the national capital.

A Union Commerce Ministry release here said that a programme is being worked out to conduct over 3,500 IPR awareness programmes in schools, universities and industries across the country, including in Tier 1, 2, and 3 cities, as well as in rural areas, along with translating content into various regional languages for a wider reach.

Earlier this week, the government extended the Start-Ups Intellectual Property Protection (SIPP) scheme for three years till March 2020 to ensure protection of entrepreneurs’ patents, trademark and designs.

China’s Huawei has applied to

China’s Huawei has applied to