Geographical Indication Registration in Madhya Pradesh

Geographical Indication is the other branch of the IPR is Geographical Indication , issues in the realm of the WTO’s Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). TRIPS defines GI as any indication that identifies a product as originating from a particular place, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristics of the product are essentially attributable to its geographical origin. Also a geographical indication (GI) gives exclusive right to a region (town, province or country) to use a name for a product with certain characteristics that corresponds to their specific location.

The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999 protect the GI’s in India. Registration of GI in India is not compulsory. If registered, it will afford better legal protection to facilitate an action for infringement which procure the rights of the Geographical origins rights .

Why Legal Protection Of Geographical Indications

Given its commercial potential, legal protection of GI assumes enormous significance. Without suitable legal protection, the competitors who do not have any legitimate rights on the GI might ride free on its reputation. Such unfair business practices result in loss of revenue for the genuine right-holders of the GI and also misleads consumers. Moreover, such practices may eventually hamper the goodwill and reputation associated with the GI.

International Protection For GI Under Trips

At the international level, TRIPS sets out minimum standards of protection that WTO members are bound to comply with in their respective national legislations. However, as far as the scope of protection of GI under TRIPS is concerned, there is a problem of hierarchy. This is because, although TRIPS contains a single, identical definition for all GI, irrespective of product categories, it mandates a two-level system of protection: (i) the basic protection applicable to all GI in general (under Article 22), and (ii) additional protection applicable only to the GI denominating wines and spirits (under Article 23).

This kind of protection is challenging, if Article 22 fails to provide sufficient intellectual property protection for the benefit of the genuine right-holders of a GI. A producer not belonging to the geographical region indicated by a GI may use the indication as long as the product’s true origin is indicated on the label, thereby free-riding on its reputation and goodwill.

History Of The Trips Provisions On GI

The Uruguay Round of the GATT negotiations began in 1986, precisely when India’s development policy making process was at a watershed. By the time India launched its massive economic reforms package in 1991, marking a paradigm shift in its policy, the Uruguay Round negotiations were well under way, paving the path towards Marrakesh in 1994 and the establishment of the WTO. India remained a cautious and somewhat passive player during the initial years of the Uruguay Round negotiations, given its long legacy of inward looking development strategy and protectionist trade policy regime.

However, at Doha India wanted to extend protection under ‘geographical indication’ (GI) beyond wine and spirit, to other products. A number of countries] wanted to negotiate extending this higher level of protection to other products as they see a higher level of protection as a way to improve marketing their products by differentiating them more effectively from their competitors and they object to other countries “usurping” their terms. Some others opposed the move, and the debate has included the question of whether the Doha Declaration provides a mandate for negotiations.

Those opposing extension argue that the existing (Article 22) level of protection is adequate. They caution that providing enhanced protection would be a burden and would disrupt existing legitimate marketing practices. India, along with a host of other likeminded countries pressed an ‘extension’ of the ambit of Article 23 to cover all categories of goods. However, countries such as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Argentina, Chile, Guatemala and Uruguay are strongly opposed to any ‘extension’. The ‘extension’ issue formed an integral part of the Doha Work Programme (2001). However, as a result of the wide divergence of views among WTO members, not much progress has been achieved in the negotiations and the same remains as an ‘outstanding implementation issue’

Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999

India has put in place a sui generis system of protection for GI with enactment of a law exclusively dealing with protection of GIs. The legislations which deals with protection of GI’s in India are ‘The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Act, 1999’ (GI Act), and the ‘Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Rules, 2002 (GI Rules). India enacted its GI legislations for the country to put in place national intellectual property laws in compliance with India’s obligations under TRIPS. Under the purview of the GI Act, which came into force, along with the GI Rules, with effect from 15 September 2003, the central government has established the Geographical Indications Registry with all-India jurisdiction, at Chennai, where right-holders can register their GI.

Unlike TRIPS], in the GI Act does not restrict itself to wines and spirits. Rather, it has been left to the discretion of the central government to decide which products should be accorded higher levels of protection. This approach has deliberately been taken by the drafters of the Indian Act with the aim of providing stringent protection as guaranteed under the TRIPS Agreement to GI of Indian origin. However, other WTO members are not obligated to ensure Article 23-type protection to all Indian GI, thereby leaving room for their misappropriation in the international arena.

The definition of GI included in Section 1(3) (e) of the Indian GI Act clarifies that for the purposes of this clause, any name which is not the name of a country, region or locality of that country “shall” also be considered as a GI if it relates to a specific geographical area and is used upon or in relation to particular goods originating from that country, region or locality, as the case may be. This provision enables the providing protection to symbols other than geographical names, such as ‘Basmati’.

Registration

While registration of Geographical Indication Registration is not mandatory in India, Section 20 (1) of the GI Act states that no person “shall” be entitled to institute any proceeding to prevent, or to recover damages for, the infringement of an “unregistered” GI. The registration of a GI gives its registered owner and its authorized users the right to obtain relief for infringement. The GI Registry with all India jurisdictions is located in Chennai with the Controller-General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks is the Registrar of GIs, as per Section 3(1) of the GI Act. Section 6(1) further stipulates maintenance of a GI Register which is to be divided into two parts: Part A and Part B. The particulars relating to the registration of the GIs are incorporated in Part A, while the particulars relating to the registration of the authorized users are contained in Part B (Section 7 of the Act).

A GI may be registered in respect of any or all of the goods, comprised in such class of goods as may be classified by the Registrar. The Registrar is required to classify the goods, as far as possible, in accordance with the International classification of goods for the purposes of registration of GI (Section 8 of the Act). A single application may be made for registration of a GI for different classes of goods and fee payable is to be in respect of each such class of goods.

In India a GI may initially be registered for a period of ten years, and it can be renewed from time to time for further periods of 10 years. Indian law place certain restrictions in that a registered GI is not a subject matter of assignment, transmission, licensing, pledge, mortgage or any such other agreement.

Rights of Action Against Passing-Off

The GI Act in India specifies that nothing in this Act “shall” be deemed to affect rights of action against any person for passing off goods as the goods of another person or the remedies in respect thereof. In its simplest form, the principle of passing-off states that no one is entitled to pass-off his/her goods as those of another. The principal purpose of an action against passing off is therefore, to protect the name, reputation and goodwill of traders or producers against any unfair attempt to free ride on them. Though, India, like many other common law countries, does not have a statute specifically dealing with unfair competition, most of such acts of unfair competition can be prevented by way of action against passing-off. Notably, Article 24.3 of TRIPS clearly states that in implementing the TRIPS provisions on GIs, a Member is not required to diminish the protection of GIs that existed in that Member immediately prior to the date of entry. This flexibility has been utilised by India in the GI Act (Section 20(2)) in maintaining the right of action against passing-off, which has been a part of the common law tradition of India, even prior to the advent of the TRIPS Agreement. Any lawsuit relating to infringement of a registered GI or for passing of an unregistered GI has to be instituted in a district court having jurisdiction to try the suit. No suit shall be instituted in any court inferior to a district court [Section 66 of the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999].

Status Of GI Registrations In India

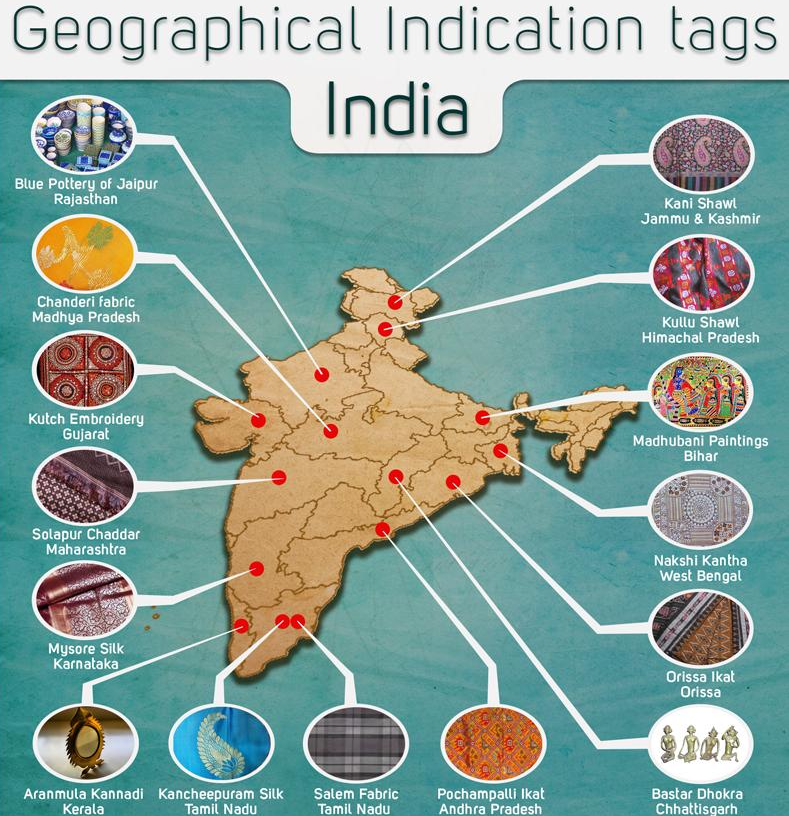

Around 610 GI’s of Indian origin have already been registered with the GI Registry as per records of year 2018 . These include GI like Maheshwar Sarees , Darjeeling (tea), Pochampalli, Ikat (textiles), Chanderi (sarees), Kancheepuram silk (textiles), Kashmir Pashmina (shawls), Kondapalli (toys), and Mysore (agarbattis).

GI’s registered during 2007-08 include ‘Muga Silk’ from Assam, ‘Madhubani paintings’ from Bihar, ‘Malabar pepper’ and ‘Alleppey Green Cardamom’ from Kerala, ‘Cora Cotton’ from Tamil Nadu, ‘Allahabad Surkha’ from Uttar Pradesh, ‘Nakshi Kantha’ from West Bengal, ‘Monsooned Malabar Coffees’ from Karnataka and Kerala. There is many more Indian GI in the pipeline for registration under the GI Act.

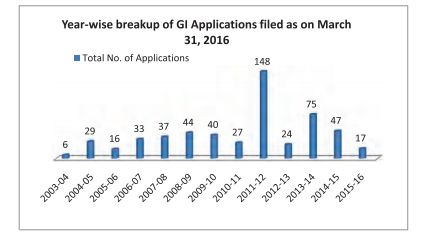

As per records of the year 2016 , total year wise applications filed for GI in India are very less –

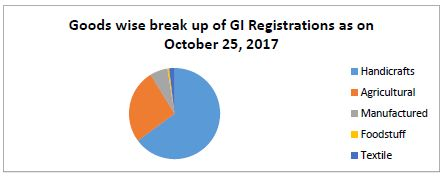

The highest number of GI in India are applied in the Handicraft –

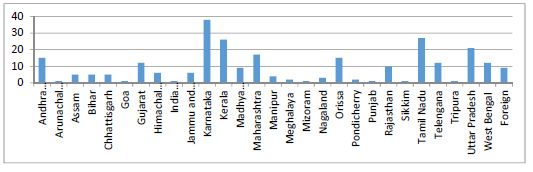

Karnatak is the leader to file highest GI application in India –